If you have a few minutes, check out my review of Tesla: A Portrait with Masks by Vladimir Pištalo. It turns out it was one of the 5 most popular reviews for February, at Washington Independent Review of Books! Color me happy!

Category Archives: miscellaneous

the Scholastic Arts & Writing Awards

I recently was a juror judging student submissions for the Scholastic Arts & Writing Awards. To read more about that experience and how you might do the same, read my post on the Awards on Potomac Review’s Blog!

‘TIS THE SEASON

Happy Chanukah. Merry Christmas. Happy New Year.

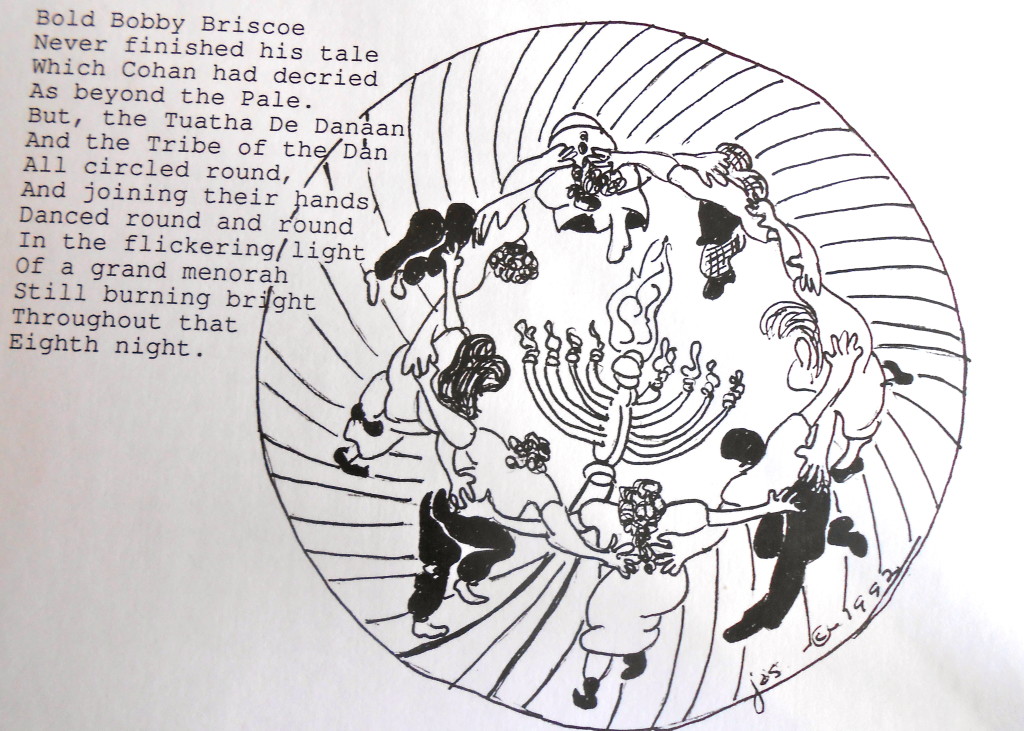

‘Tis the season, and I am lazy. So, instead of a new, original post, I shall post a playful poem published long ago in The Boston Jewish Times. Once upon a time, there was a Jewish Lord Mayor of Dublin. His name was Robert Briscoe. Briscoe had been a follower of De Valera in Ireland’s struggle for independence, and later gave advice to Palestinian Jews in their parallel struggle against British rule and for statehood. With that very brief background, I present to you:

ROBERT BRISCOE’S CHANUKAH

They had gathered for

The Feast of Lights,

And with the last

Morsel eaten,

And a drop of wine taken,

Robert Briscoe stood

And spoke.

“I’ll tell you a tale

Of raids by night.

Of daring deeds.

Of a hero’s fight.

Of battles waged

Against great armies

By the Maccabee

Of old.”

With a gasp and a sigh

The children round

Eyed him with anticipation,

While bold Bob Briscoe

Rubbed his hands

As he prepared to begin

His grand narration.

“In the time

Of Antiochus the Fourth,

And in the time

Of Henry the Eighth,

And in the time

Of George the Sixth,

If the truth be known…

The children of Israel

Had to hide behind hedgerows

To learn their aleph-bet.

For to learn one’s

Language and religion then

Could not be done

Without let

Or hindrance.”

From the back of the room

Came a familiar groan

Of a man.

“You’re telling it wrong,”

Muttered Cohen Cohan.

But, Bob Briscoe went on.

“It was forty thousand footmen

The evil king sent

To keep the Irish down,

And the Jew’s head bent.”

“Give it up!” moaned Cohan,

But, Bob wouldn’t relent.

“There were Judah, Eleazar,

And Simon, and John.

De Valera and Collins

And Begin, Dayan…”

Briscoe counted them out

On the palm of his hand.

“You’ve mixed it all up!”

Cried out Cohen Cohan.

“De Valera and Begin!

They’re not Maccabees!”

“Never mind,”said bold Briscoe,

“I know what I know.

For Begin and Dev

I’ve struck many the blow.

For Israel and Ireland

And the true rights of man…”

“But they’re not Maccabees!!”

Shouted Cohen Cohan.

Briscoe replied

With a dangerous ease,

“Who’s telling this tale

My good man, you or me?

Such a klop I should give

To the side of your head!”

“Such a klop you should give?”

Said Cohen Cohan,

His whole face turning red.

“When you turn all our

History inside out?”

Then, rejoined Briscoe

Turning about,

“Fenian, Israeli

Or bold Maccabee,

When the fight’s on

For freedom,

It’s all one to me.”

Bold Bobby Briscoe

Never finished his tale

Which Cohan had decried

As beyond the Pale.

But the Tuatha de Danaan

And the Tribe of the Dan

All circled round,

And joining their hands,

Danced round and round

In the flickering light

Of a grand menorah

Still burning bright

Throughout that

Eighth night.

© Copyright-1992-Jessie Seigel. All rights reserved.

“To Ruffle Feathers”–An Etymological Lesson at the Zoo

To “ruffle someone’s feathers” is defined as “to do something to cause confusion, agitation, irritation, or annoyance in that person.” Being a city girl, I never gave the etymology of the phrase any thought until I was visiting the National Zoo yesterday and found the flamingos in an uproar. Two human engineers had entered their enclosure to deal with some problem in the enclosure’s little artificial stream, and every time one of the humans came in or out, flamingos fled towards a far corner, flamingos made very loud noises and pecked at each other, and flamingos raised their wings as if to shepherd the rest away from the perceived danger. Each time their agitation began, the flamingos’ very neat feathers rose like heads of hair vigorously rumpled until they stand messily on end and in need of a good combing. As the engineers worked in their one spot and the flamingos calmed, their feathers settled neatly against their bodies, only to ruffle again when the engineers moved. Thus, the engineers literally ruffled the flamingos’ feathers.

Irrelevant but interesting addendum: there were also a large number of pintail ducks treading in the enclosure’s stream. Unlike the flamingos, they were unflappable. As the engineers worked, the ducks simply swam, en masse, to the side of the stream. They then waddled calmly out and stood in the grass facing the stream, attentively, but quietly waiting for the engineers to complete their work, at which time, the ducks reentered the water.

Add this as a random occurrence that can at some time inform one’s writing.

VERMONT STUDIO CENTER

Observed on April 8, 2014: A few days ago, although a low rapid gushed on the far side of the bridge, the Gihon river was mostly covered with ice. You knew water must be flowing under it, but except for a thin stream along the shorelines, the surface was white, cold, and still. Yesterday, the ice began breaking up a bit and, today, the river is suddenly flowing fast in a snake-like curve around the remaining broken ice beneath the bridge, a swirl of tiny ice-shards roiling down the middle, as the water comes. The sudden power, after the days of seeming stillness, invigorates, instilling a sense of anticipation, excitement, even danger—power now exposed, not hidden.

A green-headed wild duck darts from the sky straight at the water, but somehow ends its dive on its belly, treading water in the middle of the river, paddling against the current, moving a little upstream, and then paddling towards the shore. A piece of ice about the duck’s own size crosses its path, but just misses hitting it. My studio window gives me a good view of the flowing river.

In my short time at VSC, the resident writers (no more than sixteen of us) and artists (the balance of approximately 50 people) had a wonderful spirit of playfulness and curiosity as well as an appreciation for and encouragement of each other’s work. This was true not only within disciplines, but between them. When the writers got together for their informal readings, artists were welcome to come and listen, but also to participate if they had something written they wanted to try out. Some were fascinated to see the writer’s process–how we develop our work and analyze what we have done. Writers (at least this writer) were welcomed into studios where the visual artists were happy to take time out to talk about what they were working on and their process. I was fascinated by the visual artists’ experimentation with the tools of their various media. Just as I might play with writing devices, many of them experiment to see how one medium will affect another (eg. the effect created by spilling cleaning fluid on a color magazine photo).

Meals are communal there, and conversation at lunch or dinner, when not happily silly, often was a time when you might be asked what you were working on or how the work was going and thus given an entrée to talk out a problem you had with your work, or bounce an idea off of someone, or become inspired by an idea or problem they were working out.

In addition, during each two-week period (most artists stay for one month), there is at least one writer or poet who comes for some days as a visiting writer, gives a reading, a craft talk, and meets with those who want critique of their work. (In my two-week period, the writer was Rikki Ducornet.) Likewise, there are painters and sculptors who come to give a talk and slide show of their work and visit with visual artists who want a critique. (in my time, these were Kyle Staver and Kim Jones). The resident writers (who wish to) have an opportunity to give formal readings once per week, and the resident artists (who wish to) likewise have the opportunity to give slide shows of their work. Other than these events, we made our own fun: bonfires, roasting marshmallows, Karaoke at the local Italian bar/restaurant on a Saturday night, a Friday night dance party in the Red Mill dining hall’s downstairs lounge (organized informally), even a makeshift séance. One poet was working on a series inspired by Hitchcock’s oeuvre, and so, with her, one night, a small group of us watched a dvd of Rear Window together. And through it all, the beer, and wine, and chocolate flowed. (And coffee and tea and marshmallows and chips, too.)

The creative impulse and comradeship we found together in this month of April was far more free-spirited than I have experienced at any previous residency. I think I can speak for many of us when I say that our greatest desire is to find ways to sustain that spirit and those supportive friendships now that we have come home and back to our everyday lives.

Passing Thoughts

For me, September was a tough month filled with medical research, hours on the phone dealing various other personal and financial concerns, not to mention a troubling reaction to a vaccination I got on the first day of October, and frustrated preoccupation with the obstruction causing the federal government’s shut-down. So I did not do as much writing, or as much focused thinking on literary matters, as I would have liked, but I did do a bit of reading, and have some passing thoughts on what I read:

*****I have been reading, contemporaneously, Showing My Colors, by Clarence Page; Notes of a Native Son, by James Baldwin; and a Dover Thrift Edition of selections from the writings of Frederick Douglass, with an introduction about his life by Philip S. Foner. My impressions:

Granted, Clarence Page, a columnist at the Chicago Tribune and often a guest pundit on MS-NBC news shows, is the product of a different time and different circumstances from that of either Baldwin or Douglass, and his essays are, perhaps, attempting something different from their works. (Page might justifiably protest that he is a journalist while they were, essentially, advocates.) Nevertheless, since all three address some of the same subjects, I can’t help making the comparison and feeling that his book pales next to their works. Page’s essays suffer from what ails many modern pundits: too great an effort to sound erudite–to lean on conventional sociology, and to quote other experts, while pretending to say something original–and too little inclination to take a position on what they address. It makes such works, in the end, rather wishy-washy endeavors that use many words to tell us not much.

Baldwin, and Douglass, on the other hand–while also themselves products of very different times and circumstances–write directly and powerfully. They take my breath away (particularly, Frederick Douglass), and once I pick them up, I cannot put them down. They were true original thinkers.

*****I read a bit of Agatha Christie’s They Do It with Mirrors, and though I was not expecting great depth, I was hoping for an enjoyable escape. I was not impressed. It’s the first Christie book I’ve ever picked up, so perhaps I needed to try an earlier work. Maybe her writing got more pro forma after the upteenth book she wrote. It happens. Perhaps the National Public Television rendition of They Do It with Mirrors prepared me to expect better, but I found the writing and the characters quite thin, even for a cozy.

*****I also read a number of stories in The Selected Stories of Patricia Highsmith, and I’ve got to say, I think her work has been highly underrated. Her stories combine the cynicism of a Saki with the whimsical turns of a Hitchcock. And, in this very thick book, the stories run the gamut from mystery to domestic to science fiction to ghost stories of a sort. I particularly liked the short-short “The Female Novelist,” which takes a poke at fiction writers who are essentially self-absorbed persons writing masked autobiography. On the second page, the female novelist complains about her novel’s rejection, saying “I know my story is important!” Her husband refers to mice he has seen in the bathroom and responds: “So is the life of the mouse here, to him.” What has that to do with anything, the wife asks, and he responds: “…mice are concerned with a more important subject–food. Not whether your ex-husband was unfaithful to you, or whether you suffered from it, even in a setting as beautiful as Capri or Rapallo…” As I am sometimes fond of saying, a story about a love affair ending shouldn’t be about “my boyfriend left me,” but about the nature of love. There needs to be a connection of the particular to the universal.

******Finally, I read Pat Barker’s novel, Blow the House Down, and for gritty toughness, I’ll only say: “Take that, V.S. Naipaul, when you say women’s writing is unequal to you because of women’s “sentimentality, the narrow view of the world.” I’ll match her toughness against yours any day. Nyah. (You must picture me sticking my tongue out. And if you don’t know why I’m bringing Mr. Naipaul into this, see my post from July 2013.)

The Narrow World of V.S. Naipaul

Recently, someone brought to my attention a 2011 Guardian article reporting on a Royal Geographic Society interview with Nobel Prize Winner Mr. V.S. Naipaul. While the interview is a few years old now, Mr. Naipaul’s statements in it struck me as freshly as if the interview had been conducted yesterday. According to the article, Mr. Naipaul stated the following views:

1. that no woman writer is his literary match;

2. of Jane Austen, that he “couldn’t possibly share her sentimental ambitions, her sentimental sense of the world;”

3. that women writers are “quite different,” that “I read a piece of writing and within a paragraph or two I know whether it is by a woman or not. I think [it is] unequal to me;” and that this is because of women’s “sentimentality, the narrow view of the world;”

4. that “inevitably for a woman, she is not a complete master of a house, so that comes across in her writing, too;” and

5. that “my publisher, who was so good as a taster and editor, when she became a writer, lo and behold, it was all this feminine tosh.”

And of course, like any good bigot, in a preemptive non-apology apology, Mr. Naipaul apparently added: “I don’t mean this in any unkind way.”

For a Nobel Prize winner for literature, Mr. Naipaul seems to have an extremely narrow knowledge of literature, as well as an extremely narrow view of life. When he accuses all women writers of being sentimental or dismisses all women writers as writing sentimental tosh, one must first ask what he means by the terms “sentimentality” and “sentimental tosh.” He does not define them, so I take the liberty of assuming he means either that women write tear-jerkers (or, in American parlance, stories fit for the Lifetime channel’s made-for-T.V. movies), or that their themes are limited to women’s concerns. Taking this as my premise, I must then ask, has Mr. Naipaul ever read anything by Pat Barker? Muriel Spark? Margaret Atwood? Doris Lessing? Nadine Gordimer? Has he ever heard of them? (And as for “sentimental” tosh, has he ever read Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections? And if by “tosh” he means anything to do with what he considers women’s concerns or lot in society, is he familiar with the works of Tolstoy, Hardy, Dickens, Flaubert, or just about anything by D.H. Lawrence–all male writers? Frankly, for toughness, theme, and absence of “sentimentality,” I would set Barbara Kingsolver’s short story, “Why I Am a Danger to the Public” in her book Homeland above any of the stories in Naipaul’s Miguel Street.)

When Naipaul says of Jane Austen, that he “couldn’t possibly share her sentimental ambitions, her sentimental sense of the world,” he is baring an incapacity to make an empathetic leap into anyone’s world but his own. That is not the mark of a great writer, and certainly not of a great mind. (It is no wonder that, in Naipaul’s Miguel Street, a book of short stories about people living in poverty on Miguel Street in Port of Spain, Trinidad, not only are the subject characters of all of the stories male, but to the extent women are mentioned in the stories, they are entirely stereotypical, one-dimensional asides. The stories are quite entertaining, and Naipaul shows some sympathy for the men, but even the men are not given any depth to speak of. This was an early work, and perhaps one should examine Naipaul’s later novels to see whether he developed greater insight over time, but his public statements suggest otherwise.)

When Naipaul says he can tell within a paragraph or two that something is written by a woman, and that “…inevitably for a woman, she is not a complete master of a house, so that comes over in her writing,” he sounds a bit like the pot calling the kettle metal. In saying that a woman is not a complete master of a house, is Naipaul referring to women’s traditionally subservient position to the man of the house and to men in society? If one is not master, is one then a servant or a slave or–dare one say–subject to some form of colonial rule? On those terms, anyone–man or woman–who comes from an oppressed or colonized group or place and chooses that subject as a theme, and those people as characters–must have a narrow world view. This, then, must apply to Mr. Naipaul’s choice of themes and characters as well.

Finally, to bolster his universal dismissal of female writers, Naipaul pulls out his anecdotal view that his female editor is a good editor but, when she wrote, sure enough–she wrote “all this feminine tosh.” To that, I would say, first, that given his prejudices, Mr. Naipaul is hardly a reliable source for such an assessment. But even if he is correct, editing and writing are two very different tasks. Many people, male and female, can do one well and not the other. Many people, male and female, want to write but find they do not really have something of consequence to write about.

This gentleman won the Nobel Prize for literature. It is reported that some have dubbed him “the greatest living writer of English prose.” I have not yet discovered who so-dubbed him, so I cannot vouch for whether those proclaiming that greatness are giving a sincere assessment or are part of the usual publicity campaign found in the publication industry. But, considering that there are some other great writers, male and female, currently living, to dub any one of them the “greatest” seems a bit of puff. Still, I wouldn’t begrudge him as much claim as anyone else to the title, but for his using his position, standing on these laurels, real and/or manufactured, to dismiss as inferior all literature written by a gender other than his own.